Haim Steinbach: creature: Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York

Steinbach is specifically interested in the figure’s role in contemporary art, as well its evolution throughout culture and history. Investigating notions of character, the artist explores the figure as a representation of the human creature within its own narrative frame, and within the “inter-narrative” created by and with the other figures and objects.

Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is pleased to present its first solo exhibition of work by acclaimed artist Haim Steinbach.

Haim Steinbach raises everyday objects to the level of art. He explores the common social ritual of collecting, arranging and presenting objects, in turn discovering the psychological and cultural context of the object. Steinbach’s work has radically redefined the status of the object in art, and has had a far-reaching influence on the growth of post-modern artistic dialogue. This exhibition continues Steinbach’s interest in the choices involved in and implicit in display, and the meanings and associations of our individualized, mass-produced and collective culture.

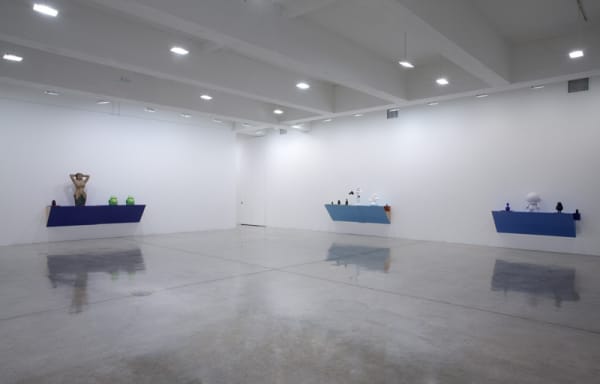

On the first floor, Steinbach presents works that feature a sweeping spectrum of materials both mass-produced and unique. The artist incorporates such diverse items as a hand crafted Mr. Peanut folk art statue, Star Wars collectibles, plumbing pipes, an editioned Munny figurine, tree growth, toy dog chews and other found items. The repetition and deliberate placement of each object lends to its elevation from mundane item into artistic material interacting with the shelf, the wall, and the architecture.

One of the show’s overarching themes, which is reflected in the exhibition title creature, is the investigation of the figure. Steinbach is specifically interested in the figure’s role in contemporary art, as well its evolution throughout culture and history. Investigating notions of character, the artist explores the figure as a representation of the human creature within its own narrative frame, and within the “inter-narrative” created by and with the other figures and objects.

Also at work is a subtle investigation of stories, from mermaid tales to the Star Wars epic, and even Steinbach’s own personal stories (eg. a chair and stool from the artist’s home). Through narrative subtext, the objects transcend commodification, while their tangible physicality still plays a primary role. Per Steinbach, “Materiality is very important (to my work), that objects have a particular materiality, cultural and innate - whether it be wood, ceramic, plastic, etc.”

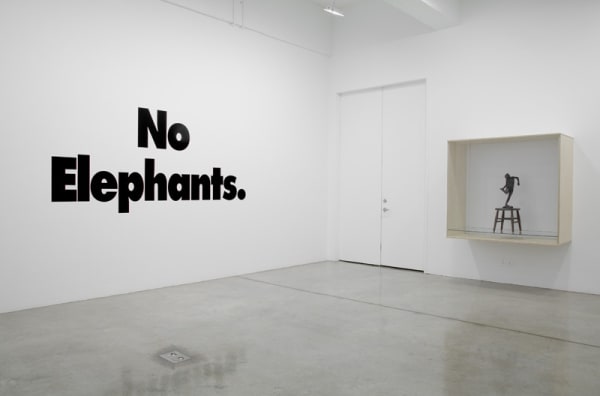

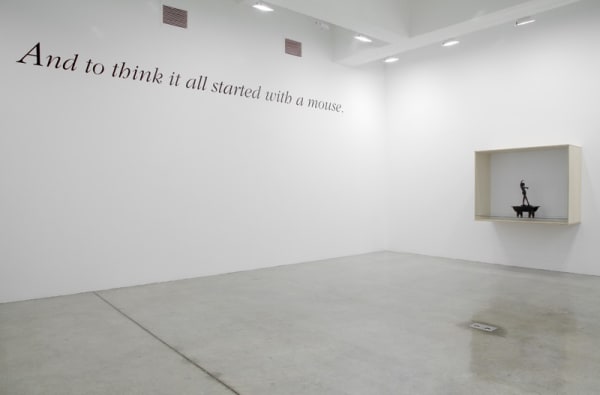

In the rear gallery, large black vinyl wall text reads “No Elephants” and on the opposite wall states “And to think it all started with a mouse.” Two pristine boxes feature small-scale copies of Degas dancers. These museum souvenir figurines made of faux bronze rest atop his antique stools. The texts and sculptures suggest a variety of ideas related to scale and contrast, and, opposed to the plastic, wood and metal figures on the shelves in the main gallery, the dancers evoke different connections to history, art history, and class.

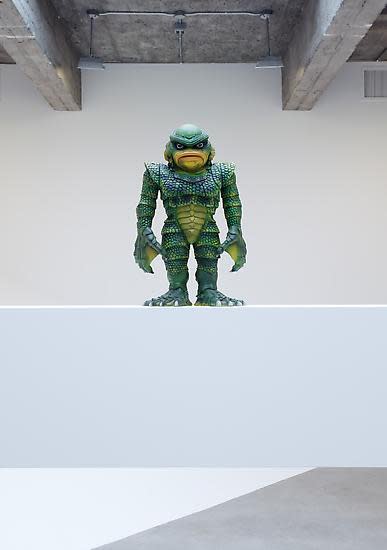

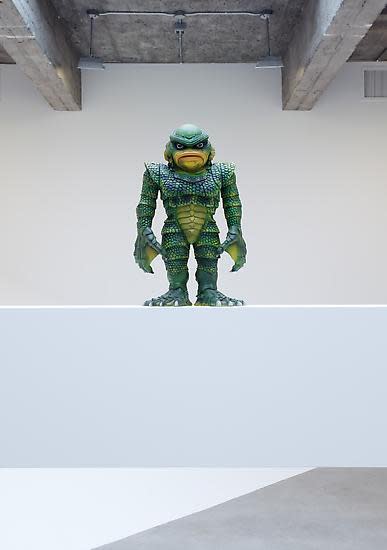

Upstairs, a dramatic reconfiguration and contextualization of the space uses the gallery as a box for display, but also as architecture, expanding our concept of exhibition and the human relationship to space in general. The large pyramid-like wedge, possibly a nod to the Mexican architect, Luis Barragán, or even Incan architecture, uses an incline to change the vanishing point. The opposite corner, in relation to this Euclidean mass, gains prominence through contrast, drawing the viewer in. Beneath the skylight, on a large beam that hovers and divides the room, a “Creature from the Black Lagoon” figurine appears to have just landed from outer space. Here, objects and architecture all interact with each other, resulting in a reorientation of our senses and a re-identification of perspective.

In the upstairs project gallery, a diagonal wall breaks up the square shape of the room. White lettering on a black rectangle reads, “You don’t see it, do you?” This provocative text touches on the boundaries of language, of feeling versus structure, and of perception. The text challenges the viewer as to what is being discussed, as well as expectations about what one is looking for when entering an art gallery.

This and other wall text pieces in the show propose that reading is an act of seeing, and that graphic codes which proliferate our current media culture accustom us to word and image arriving in the same package. Just as the shelving of objects reminds viewers that display is an ideological enterprise, Steinbach’s wall paintings of vernacular text serve also to play with established codes of interpreting what is seen.

Finally, the exposure of building materials on the second floor – exposed wall supports, unpainted sheetrock – compels the viewer to consider the concept of decorative architectural surface. In Steinbach’s view, “The surface of walls and objects is a cultural material – it’s a language that speaks of who we are and how we think.” The artist shows how wall paint is a “skin” of sorts that we take for granted, a cultural phenomenon that is universally accepted as a given. Steinbach is calling attention to this philosophical idea, one of perception and illusion.

Further, the artist also draws our attention to the relationship between function and the imagination and how design plays on the subconscious, especially in the nascent stages of an idea. Steinbach is interested in the mysterious places that go unnoticed by adults - the space behind the toilet, a hole in a wall, a nook under the stairs. These spots are imbued with a fantastic, psychological energy that is generally accepted as the fodder for dreams, but unknowingly occupies a greater role in our conscious life. As the mind collects patterns and matches disparate images to form original thoughts, new ideas make their way into our reality. For example, a designer tapping into such connections might be compelled to design a prototype for a piece of hardware as common as a gate valve based on something as obscure as the vertebra of a mastadon. One such industrial gadget can be found in the gallery. At the same time, works in the creature exhibition illustrate that the function/imagination relationship is a two-way cycle where functional objects inspire the seeds of imagination, and such ideas blossom into artistic vision.

Steinbach’s work is in numerous museum collections including the Guggenheim Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Menil Collection, Houston, Texas, the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, as well as the Stedelijk Museum, Castello di Rivoli, Staatsgalerie Stuttgart and the Tate Modern. Current and upcoming exhibitions include If You Lived Here, You’d Be Home by Now at Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, June 25 – December 16, 2011; Postmodernism: Style and Subversion at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, September 24, 2011 – January 8, 2012 and This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, February 11 – June 3, 2012, which will travel to the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis from June – September 2012 and to the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston from October 2012 – January 2013. A catalog will be published in conjunction with the exhibition.

All installation images above: Photo by Jean Vong