MARK MANDERS: ISOLATED ROOMS: ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO AND RENAISSANCE SOCIETY, UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

The Art Institute of Chicago and The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago will co-present a single, ambitious exhibition of new sculptures and drawings by Amsterdam-based artist Mark Manders this fall. The project, entitled Isolated Rooms, will be on view at the Art Institute from September 13, 2003 to January 4, 2004, and at The Renaissance Society from September 14 to November 2, 2003. This two-part exhibition is the Dutch artist’s first one-person museum exhibition in the United States. It also marks another remarkable collaboration between the Art Institute and The Renaissance Society following the Thomas Hirschhorn exhibition in 2000 two venues that share a commitment to bring the very best in international contemporary art to the city of Chicago.

Manders belongs to a generation of post-minimal sculptors whose work is unabashedly grounded in narrative. In this respect, his significant precursors include Robert Gober, Juan Munoz, Kiki Smith, and Miroslaw Balka, to name a few. Manders, however, uses the figure sparingly, relying instead on alterations and configurations of everyday objects and architectural fixtures to create disturbingly quizzical tableaux and installations that evoke the feeling of absence rather than presence. Subjectivity and identity are questioned rather than asserted through naturalistic rendering of the human form. Although interested in narrative, Manders’ generation has inherited, via figures such as Bruce Nauman, a healthy skepticism regarding the time-honored creed of breathing life into inert materials. Stripped of such noble sentiment, sculptors no longer partake in a positivist anthropomorphism, converting objects into organisms; instead organisms are rendered as objects.

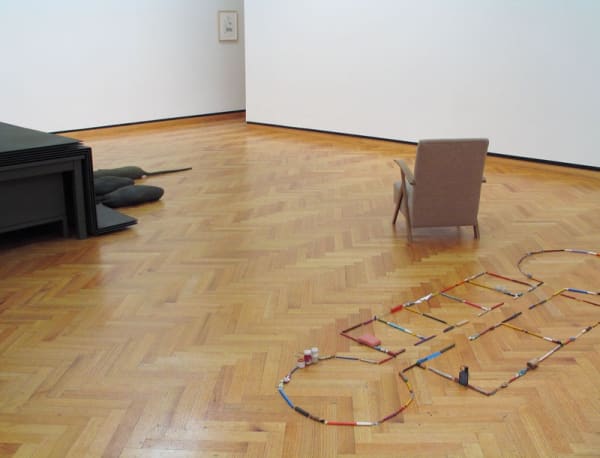

In Manders’ case, the organism is the self and the object is a series of rooms that amount to a building, or what he has dubbed Self-Portrait as a Building, an ongoing project that the artist has developed over the past 17 years. This project, a piece of purely imaginary architecture, represents a larger, perpetually unrealized whole. Dozens of rooms are designated to contain Manders’ many handmade artifacts and objects. For the artist, small provisional floor plans reveal the locations of all objects and their precise juxtapositions within the context of the larger project. The framework provides the artist with a system of coordinates, an archive, an encyclopedia of references and meanings, and a forum for experimentation, all in one.

Manders makes no distinction between the figure and the figurative, the figurative and the literal, the literal and the literary. His sculptural vocabulary can be read and its parts recombined with new work to form open-ended verse that change from one exhibition to the next, and are exhibited in fragmentary statesas is the case with Isolated Rooms. The work is driven by poetic narratives whose syntax consists of ideas and personal experiences rendered in discreet object form. It does not, however, function as hermetic, self-referential poetry as much as it does a rhetorical, bleak humor. Manders’ poignant object choices, with their references to office, factory, alley, laboratory, or cinderblock hut, conjure an all too familiar alienation, one that hints at Franz Kafka’s absurdist bureaucracy, George Orwell’s utterly instrumentalized humanity, or the humorous intellectual dry heaving characteristic of, say, Samuel Beckett. Manders’ rodent, a recurring motif, has assumed varying degrees of representation with his installations, from the inclusion of actual taxidermied rats to large, abstract, biomorphic rat-like forms. It recalls a line from the French poet Paul Celan that, “There are still songs to sing beyond humankind.” Likewise, Manders’ vision suggests a post-humanist world in which questions of who we are, only be arrived at through a consideration of what we are, as gleaned through the settings and objects we make of ourselves and for ourselves.