Blaffer Art Museum is the exclusive North American venue for Mirrors for Princes, an evolving five-city exhibition of installations and sculpture by the art collective Slavs and Tatars. Following presentations in Zurich; Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; Edinburgh, Scotland; and Brisbane, Australia, the exhibition concludes its international tour at Blaffer, where it is on view Jan. 15-March 19, 2016.

Mirrors for Princes takes its title from a medieval genre of advice literature for rulers that offered instructions, aphorisms, and reflections on how to rule a nation, from economics to etiquette, astrology to agriculture. The mirrors-for-princes genre, whose most famous examples include Machiavelli’s The Prince and Al-Ghazali’s Nasihat al muluk, operated as a poetic form of political critique in both Christian and Muslim lands during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance while carving out a space for statecraft at a time when most scholarship was devoted to religious affairs.

Using the genre as a conceptual framework, the works on view translate literary tropes and vernacular objects, such as religious furniture or cosmetic tools, into artworks that further Slavs and Tatars’ investigation of speech and sovereignty.

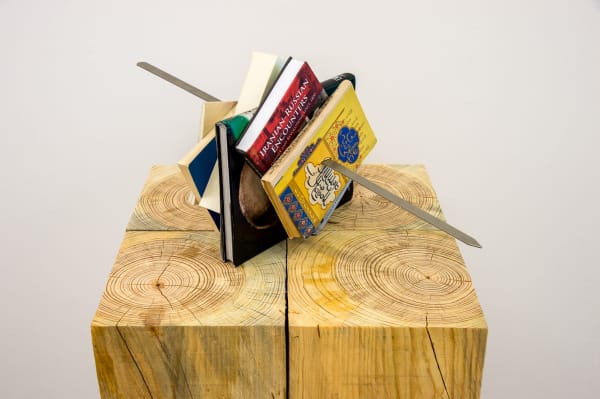

Lektor (2014), a six-channel audio installation, features excerpts from an 11th-century Turkic “mirror for prince” called Kutadgu Bilig (Wisdom of Royal Glory) in as many languages (Uighur, Polish, German, Arabic, Gaelic and Spanish). Excerpts from the poem advising on the power and pitfalls of the tongue play on speakers whose forms echo that of a rahlé, a foldable, X-shaped bookstand used for holy texts.

Another gallery reveals a series of glowing, fetishistic sculptures evoking the Kutadgu Bilig’s concern with grooming. Through a witty blend of academic tropes and pop vernacular, these works suggest parallels between the mirrors-for-princes genre and contemporary self-help books. Instead of describing the inner lives of narcissistic individuals, how can subjectivity be defined as a multitude of peoples, nations, conflicting desires, and intentionalities?

Where the literary proposals of the original mirrors for princes contemplate the divisions between self and other, male and female, sacred and profane, Slavs and Tatars’ turn to everyday ritual casts governance as self-governance, a universe of ambiguities, or in their own words: “the heart and art of politics.”