Tanya Bonakdar Gallery is pleased to present Karyn Olivier’s first solo exhibition with the gallery, At the Intersection of Two Faults, on view in New York from June 25 through July 30, 2021.

Karyn Olivier’s artistic practice merges multiple histories and collective memory with present-day narratives. Manipulating familiar objects and spaces, the artist re-contextualizes the viewer’s relationship to the ordinary. Questioning what we presume to be the function or “facts” of an object or space, she asks us to reconcile memory with conventional meanings, ultimately revealing contradictions and dualities as well as new possibilities and ideas. Olivier’s work often reflects on public versus private space or the exterior versus the interior, recalling communal nostalgias connected to social and physical experiences and how those phenomena relate to inclusivity and acceptance.

How we interact with and dissect conflicting narratives and their representation in art are core explorations of Olivier’s practice. With recurring themes of absence, invisibility and displacement often embedded in the viewing experience itself, the artist draws attention to these concepts both physically and emotionally. Tethering the formidable and fragile, melancholy and hope, Olivier’s work echoes the tension that exists in our shifting personal and public lives.

At the entrance of the exhibition are multiple works comprised of salvaged asphalt roofing. Created from processed petroleum brought up from the earth beneath our feet to function as roofs above us, these discarded pieces have been reimagined and repositioned. From the earth to the sky, the floor of Olivier’s studio to the gallery wall, this discarded tar functions both as a map and a window, welcoming visitors and inverting the material’s practical functions to reveal unexpected commonalities.

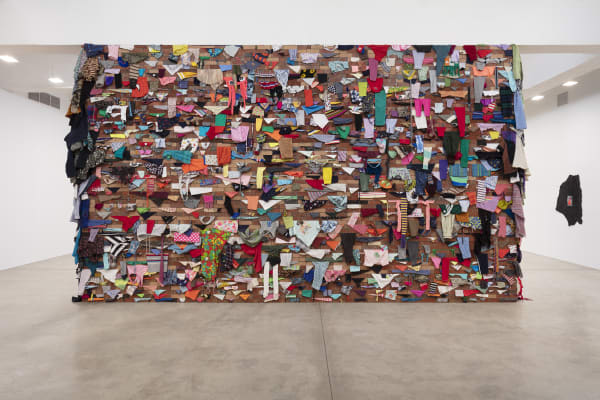

FORTIFIED stands at the front of the main gallery. Spanning 20 feet in length and 12 feet in height, its physicality and weight are immediately felt. As the viewer approaches the monumental wall, we also sense its instability. Instead of mortar, used clothing holds the structure together — colorful sleeves and patterned socks protrude through the gaps between the bricks. Each article of clothing becomes evidence of a crushing burden, born individually and together. Bits of sweatshirts, pajama legs, dress shirts, track pants, dresses are recognizable — each scrap’s purpose and fabric invoking a life, a place, a journey, a loss. The wall proposes as many questions as it answers — is it a shelter, a protector, a barrier, a divider, a border? As the viewer circles the sculpture, a tsunami of whole garments appears, inescapable surrogates for the body.

In THE BODY WAS THE HOME THAT MATTERED (Monument) strips of layered clothing are draped from a burnt and charred fence post inviting consideration of fire and its contradictions—regenerative and destructive, cleansing and polluting, a welcome home and a murderous barrier. In HOW MANY WAYS CAN YOU DISAPPEAR a massive entanglement of colorful pot warp rests in a corporeal heap upon the floor. An array of buoys dangle above the mass, hanging from a rope cast of salt, serving as witness and memorial. The lines and twisted metal traps they mark call to mind other detritus, other bodies washed ashore by sea migrations.

In the rear gallery space, a dissected hoodie is draped on a coat rack fashioned from an old and worn coal shovel handle. Its simple lines support the garment’s bodiless, dissembled shape. The absence of the figure becomes emblematic, a literal and metaphorical reference to mortality. Relating to concepts of human loss, grief and the need for racial justice in our troubled democracy, FALSEHOOD (Cape) reflects this void, both physically and emotionally.

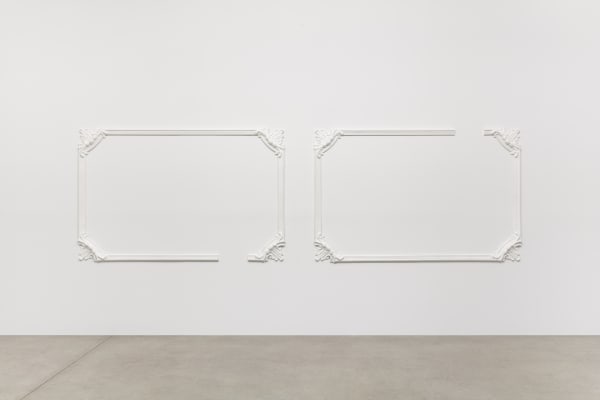

RIFT RIFF presents two ornate moldings, cast to appear like plaster, adorning the back wall. They feature the embellished flourishes of a specific but unknown interior space. A clean break in each frame upsets meaning and symmetry. What can we extrapolate about the missing parts based on the whole?

Exploring the relationship between interior and exterior spaces, this room also merges architecture and the domestic space with the natural world. In J’OUVERT (Seed Stage), a 1960s Italian chair rests on a heap of confetti-covered earth. The brightly colored costume fragments evoke the remains of a carnival or festival, the aftermath of a celebratory event that now litters the soil like seedlings. In POWER LINE, a gnarled yet smooth knot of wood, hollowed and polished by nature, is suspended from a gold-leafed metal rod that runs between two walls. Inspired by the tree chunks often left hanging between overhead power and phone lines, Olivier plays with the absurd beauty of these unintentional tree memorials, sacrificed to keep communications and commerce functioning.

Olivier was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1968, and was raised in the United States. She received an M.F.A from Cranbrook Academy of Art and a B.A. from Dartmouth College.

This year Olivier received the RAIR (Recycled Artists in Residency) Fellowship Residency. She has been the recipient of the Rome Prize (2018), the New York Foundation for the Arts Award (2011), the William H. Johnson Prize (2010), the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship (2007), the Joan Mitchell Foundation Award (2007), and the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation Biennial Award (2003).

Important solo exhibitions include Everything That’s Alive Moves at Institute of Contemporary Art in Philadelphia (2020) which traveled to University of Buffalo Art Gallery (2021) and A Closer Look at Laumeier Sculpture Park in St. Louis (2007). The artist’s work was featured in the Busan Biennial, Korea (2006) and Gwangju Biennial (2008). Olivier’s work has also been included in notable group exhibitions at the Ulrich Museum of Art (2013); World Festival of Black Arts and Cultures in Dakar, Senegal (2010); Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston (2007); Whitney Museum of Art, New York (2006); Studio Museum in Harlem (2005); MoMA P.S.1 (2005); Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (2004); SculptureCenter, New York (2004), and Mattress Factory (2006), among others.

Olivier has a long career of working in the realm of public art. In 2018, the artist unveiled Witness, a permanent commission at the University of Kentucky recontextualizing previous artworks and histories on the university’s campus. In 2017, Olivier completed a large-scale commissioned work, The Battle is Joined, for Monument Lab in Philadelphia’s historic Vernon Park. In 2015, she created a site-specific work in New York City’s Central Park for the Creative Time exhibition Drifting in Daylight,as well as a permanent sculpture for Long Island City’s Hunter Point South Park entitled Tetherball Monument, sponsored by NYC’s Percent for Art program. Olivier was selected to create a new memorial at Stenton Park in Philadelphia, honoring Dinah, a former enslaved woman who saved an historic mansion from burning by the British in the Revolutionary War. Her most recently awarded commission will commemorate the rediscovery of Bethel Burying Ground in Philadelphia, where five thousand African Americans were buried in the early 1800s when Black people were denied dignified graves.

Karyn Olivier’s work can be found in the permanent collections of Museum of Fine Arts, Houston and The Studio Museum in Harlem.

All installation images above: Photo by Pierre Le Hors

-

Karyn Olivier, PARLATUVIER (Expansion), 2021

Karyn Olivier, PARLATUVIER (Expansion), 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, Fortified, 2018-2020

Karyn Olivier, Fortified, 2018-2020 -

Karyn Olivier, HOW MANY WAYS CAN YOU DISAPPEAR, 2021

Karyn Olivier, HOW MANY WAYS CAN YOU DISAPPEAR, 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, THE BODY WAS THE HOME THAT MATTERED (Monument), 2021

Karyn Olivier, THE BODY WAS THE HOME THAT MATTERED (Monument), 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, MAGIC CARPET, 2021

Karyn Olivier, MAGIC CARPET, 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, POWER LINE, 2021

Karyn Olivier, POWER LINE, 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, FALSEHOOD (Cape), 2021

Karyn Olivier, FALSEHOOD (Cape), 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, RIFT RIFF, 2021

Karyn Olivier, RIFT RIFF, 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, J'OUVERT (Seed Stage), 2021

Karyn Olivier, J'OUVERT (Seed Stage), 2021 -

Karyn Olivier, 363 DAYS (Soon come), 2021

Karyn Olivier, 363 DAYS (Soon come), 2021