The Benin artist Meschac Gaba first conceived the Museum of Contemporary African Art during his 1996–7 residency at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten in Amsterdam. He describes finding ‘another reality’ when visiting museums in Europe, a reality in which he could not imagine how the art he wanted to create could be integrated: ‘I needed a space for my work, because this did not exist.’

Gaba has claimed that the Museum of Contemporary African Art is ‘not a model… it’s only a question.’ It is temporary and mutable, a conceptual space more than a physical one, a provocation to the Western art establishment not only to attend to contemporary African art, but to question why the boundaries existed in the first place.

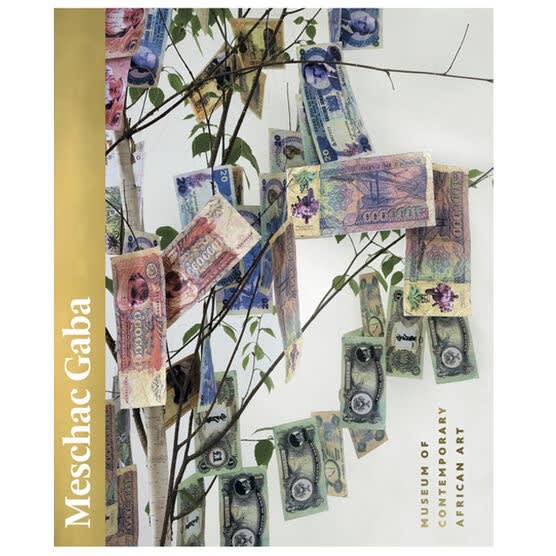

Before leaving the Rijksakademie in 1997 Gaba presented the first part of his project, the Draft Room. Prefiguring many of the conceptual concerns and the aesthetic approach that Gaba would develop in later rooms, the Draft Room contained an unusual assortment of handmade, found and altered objects. There were several works made from decommissioned banknotes, as well as heaps of ceramic foods that reflected his astonishment at the excessive overproduction in Europe.

Over the next five years further rooms would appear, one by one, in exhibitions and museums internationally. Some rooms, such as the Library, Museum Restaurant and Museum Shop, are familiar elements of most contemporary Western art museums. However, by placing these traditionally subsidiary activities at the heart of his project, Gaba calls into question the nature and function of the museum and our relationship to it. By supplementing these sections with others, such as the Humanist Space, Marriage Room, Game Room and Music Room, Gaba’s museum is a space not only for the contemplation of objects, but for sociability, study and play in which the boundaries between everyday life and art, and observation and participation are blurred.

The Art and Religion Room brings together religious artefacts and everyday objects arranged side by side on a large, cross-shaped wooden structure. Referencing the long relationship between art and religion across cultures, this room also mimics contemporary Benin, where Gaba explains most people are poly-religious: ‘Catholics brought Christianity, but for my ancestors Catholicism and Voodoo are not different… You will see sculptures of angels, of Jesus Christ and Mami Wata all in the same house.’

While Gaba broaches many serious questions in his Museum of Contemporary African Art, his approach is in equal parts sincere and playful. On 6 October 2000, invited guests and ordinary visitors to the Stedelijk Museumin Amsterdam witnessed the marriage of Meschac Gaba to Alexandra van Dongen. Well-wishers brought presents, which, together with the bride’s wedding dress, veil, shoes and handbag, their marriage certificate, guest book and wedding photographs and video, feature in the Marriage Room. Here art and life are indistinguishable and the relationship between viewer, art object and artist is reappraised.

The desire, in the artist’s words, ‘to share my fantasy’ continues throughout many of the twelve rooms. In the Salon visitors are invited to play the Adji computer game, an adaptation of the traditional African game Awélé. In the Architecture Room the public can build their own imaginary museum using wooden blocks, and in the Game Room gallery goers are able to play with sliding puzzle tables, reconfiguring the flags of Chad, Angola, Algeria, Senegal, Seychelles and Morocco.

While interactivity is a crucial part of this project, collaboration is equally so. Other artists have contributed objects to the Museum Shop, and have prepared and hosted dinners in the Museum Restaurant; the role of curators is enshrined in the Library with a ‘curators’ table’, and in the Architecture Room there is a ladder with colourful plexiglass treads inscribed with the names of the institutions and organisers who have presented Gaba’s project.

When the last-completed section, the Humanist Space, was first presented in 2002 at Documenta 11 in Kassel, visitors could use the gold bicycles to navigate the city. It was a fitting culmination to the Museum of Contemporary African Art, extending its reach out of the museum and into the street.